A new scientific study has uncovered intriguing genetic activity in a group of polar bears in southern Greenland that could shed light on how some animals respond to rapid environmental change. Researchers found evidence that so-called “jumping genes” are more active in these bears’ DNA — a discovery that may help explain differences in how this isolated population copes with warmer conditions and diminishing sea ice. As the Arctic continues to warm at an alarming pace, this research provides fresh insights into the complex interplay between genetics, climate stress and animal survival.

What Are “Jumping Genes” and Why They Matter

“Jumping genes,” scientifically known as transposable elements, are segments of DNA that can move from one location in the genome to another. Unlike most genetic material that remains fixed, these mobile elements can influence how nearby genes are turned on or off. This can affect traits linked to metabolism, stress response and other functions vital for survival. In many species, including humans, transposable elements make up a significant portion of the genome and can play roles in evolution and adaptation.

In polar bears, researchers have discovered that these elements are particularly active in individuals inhabiting southeastern Greenland — a region that experiences comparatively warmer temperatures than the high Arctic. The heightened activity of these genetic elements may be associated with changes in physiological processes, such as how bears handle heat stress or metabolize fats when traditional hunting patterns are disrupted.

The Southern Greenland Population: A Unique Subgroup

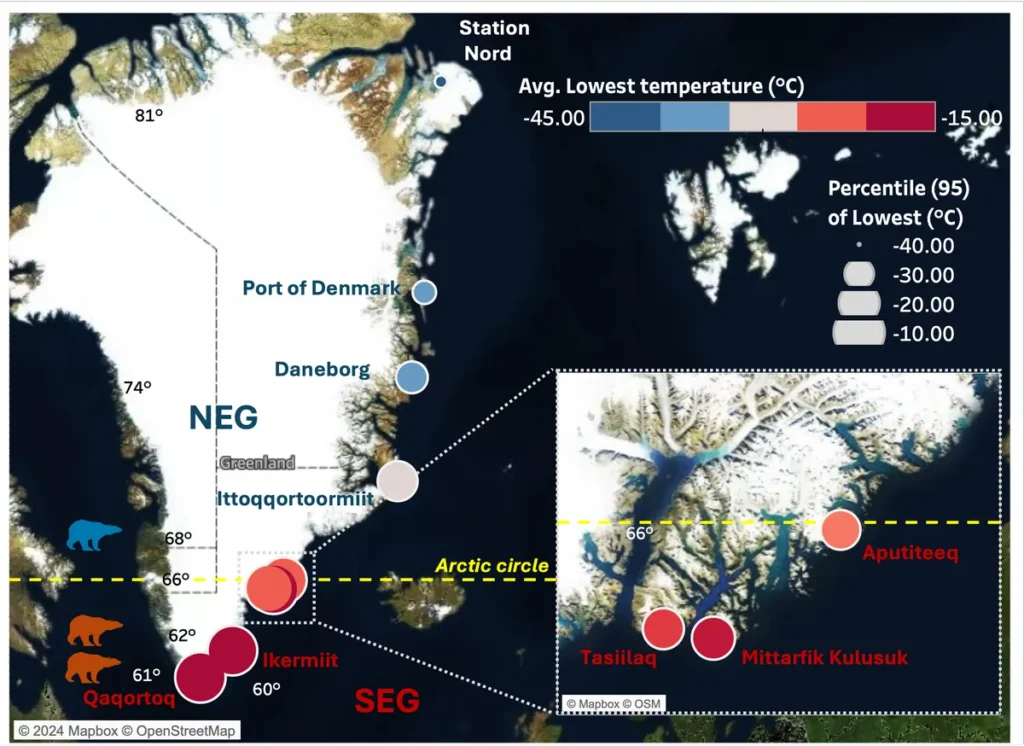

Polar bears typically rely heavily on sea ice as a platform for hunting seals, their primary food source. However, the population in southeastern Greenland has been living with reduced sea ice for generations. Scientists believe this group became isolated from their northern counterparts around 200 years ago, giving them a distinct genetic identity shaped by both geography and local climate conditions.

These southeastern bears differ not just in their habitat but in their behavior and range use. Unlike other Arctic bears that travel vast distances on sea ice, the southeastern group tends to stay closer to shore and may exploit alternative food sources and hunting strategies, including relying on glacial mélange — a slushy mix of ice that can form in fjords and provide a stable platform much of the year.

Genetic Shifts Linked to Climate and Diet

The new research compared blood samples from 17 adult polar bears — 12 from cooler northeastern Greenland and five from the warmer southeast — to examine how genetic activity varies with local climate. The key finding was that the southeastern bears exhibited significantly more transposon activity, particularly in genes connected to heat stress response, metabolism and fat processing. These genetic shifts could be a response to the challenges posed by warmer environments and changes in food availability.

In addition to coping with temperature stress, the southeastern bears may be adjusting to diets that include less of the high-fat seal blubber typical of northern polar bear diets. Changes in fat processing genes could reflect this shift, hinting that these animals are finding ways to survive with different nutritional resources.

What This Tells Us About Adaptation in Rapidly Changing Environments

While the phrase “rewriting their own DNA” can sound dramatic, scientists emphasize that what’s happening is an increase in the activity of existing DNA elements that may influence how genes function. This kind of genetic flexibility could represent a short-term mechanism by which organisms respond to rapidly changing environments, even if it doesn’t constitute long-term evolution in the traditional sense.

Such responses are especially relevant in the Arctic, where temperatures are rising faster than nearly anywhere else on Earth. Polar bears across the region face shrinking sea ice and increasingly unpredictable conditions, making any potential adaptive mechanism — genetic or behavioral — a subject of intense interest for conservationists and biologists alike.

Caveats and Conservation Implications

Despite these intriguing findings, scientists caution that increased activity of jumping genes is not a guarantee of survival for polar bears as a species. The study’s authors point out that while genetic changes might help some individuals cope locally, they do not mitigate the broader threats posed by climate change, such as habitat loss and declining prey availability. Sustained action to reduce global warming remains essential to the long-term survival of polar bears.

Moreover, the isolated nature of the southeastern Greenland population raises questions about genetic diversity and resilience. Small, isolated groups can be more susceptible to inbreeding and other genetic challenges, potentially limiting their ability to adapt to future changes. Preserving a wide range of genetic diversity across polar bear populations is therefore a key priority.

What Scientists Plan Next

Future research aims to deepen understanding of how genetic mechanisms like transposable element activity are linked to environmental stressors and fitness outcomes. By tracking changes over time and across different polar bear populations, researchers hope to better predict how species will respond to ongoing climate shifts and which populations are most at risk.

These insights could inform conservation strategies, from identifying critical habitats that need protection to anticipating how dietary shifts might influence population health. While genetic flexibility offers a glimmer of hope, scientists underscore that it must be paired with urgent global efforts to curb climate change.

The discovery of heightened “jumping gene” activity in southern Greenland’s polar bears adds a fascinating chapter to our understanding of how wildlife reacts to rapid environmental transformations. Although these genetic responses provide new avenues for study, they do not replace the urgent need for climate action to preserve the Arctic ecosystem. As researchers continue to unravel the genetic and ecological complexities of polar bear adaptation, the broader story remains one of resilience under pressure — but also of vulnerability in the face of unprecedented warming.