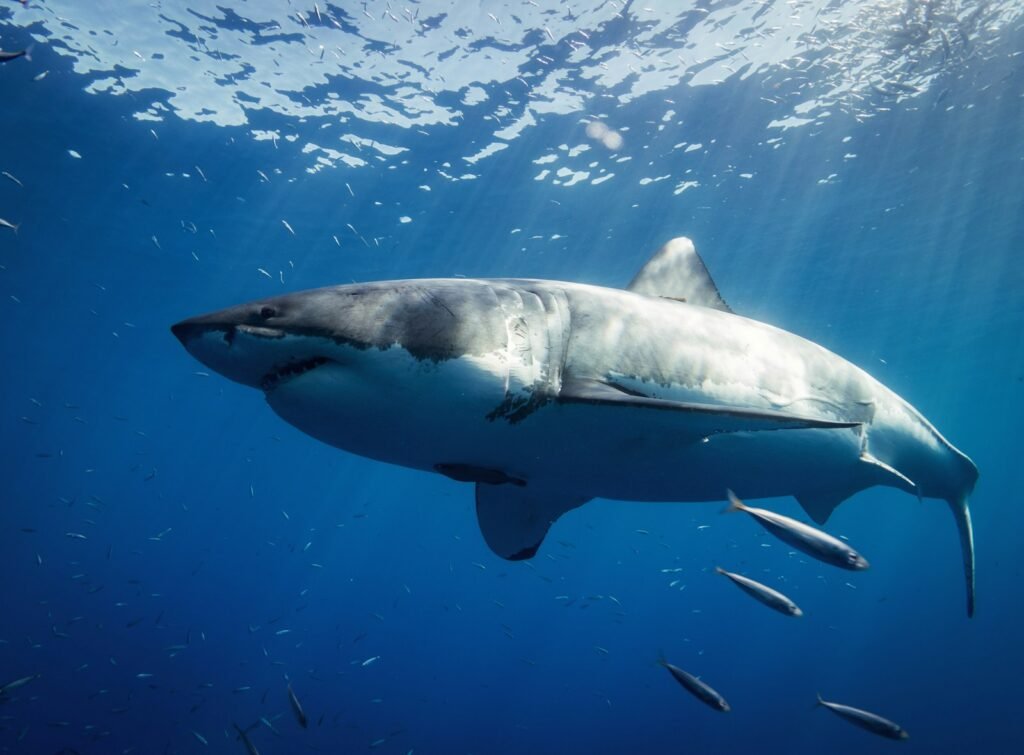

The Mediterranean Sea, a cradle of maritime culture and a nexus of biodiversity, is now the setting for a troubling chapter in marine conservation. Once roaming these warm waters in numbers that supported a complex food web and balanced ecosystems, great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) now teeter on the brink of local extinction. Scientists and conservationists are sounding the alarm: without immediate, coordinated action, this apex predator could vanish from the Mediterranean Sea entirely. The decline of great whites isn’t just a loss of an iconic species — it signals deep, systemic issues affecting one of the world’s most exploited marine environments.

A Rapid and Troubling Decline

Recent research indicates that great white sharks in the Mediterranean have suffered dramatic population losses over recent decades. These sharks are now classified as Critically Endangered in the region, with estimates suggesting their numbers have dropped by more than half — and in some areas by as much as 90 percent compared to historical levels. Such declines are rarely accidental; they are the cumulative result of prolonged fishing pressure, both legal and illegal, in waters where governance and enforcement have long struggled to keep pace with exploitation.

The Mediterranean’s status as one of the most heavily fished seas on the planet has deep historical roots. For centuries, coastal communities have relied on marine resources, but industrial-scale fishing in the 20th and 21st centuries has pushed many species to the edge. Great whites, with their slow growth, late maturity, and low reproductive rates, are particularly vulnerable. Once abundant, they are now so scarce that scientists have struggled even to find individuals for study — a stark indication of their dwindling presence.

Illegal Fishing: A Persistent Threat

Despite regulatory frameworks intended to protect great white sharks, illegal fishing remains pervasive across the Mediterranean. In 2025 alone, monitoring efforts recorded at least 40 confirmed deaths of protected great white sharks in North African ports — a number that researchers say could underestimate the true toll.

These sharks often turn up in fish markets despite international agreements that ban their capture, sale, or display. Footage from Tunisia and reports from conservation groups reveal that even with protections on the books, enforcement is inconsistent. Many fishers target sharks deliberately for meat and fins, while others catch them accidentally as bycatch. These deaths weaken already frail populations and underscore the gap between policy and practice.

The continuing presence of shark products in markets highlights a central enforcement challenge: even strong laws are ineffective without robust monitoring and compliance mechanisms. Experts argue that involving local fishing communities in conservation efforts, providing alternative livelihoods, and strengthening legal frameworks are crucial steps toward reducing illegal catches.

Ecological Role and the Consequences of Loss

Great white sharks are apex predators — they sit at the top of the food chain and help regulate the health of marine ecosystems. By preying on large fish, seals, and other predators, they help maintain balanced populations below them in the food web. Their disappearance from Mediterranean waters could ripple outward, destabilizing food webs and altering community structures in unpredictable ways.

Historically, these sharks roamed widely across the basin, from the Strait of Gibraltar through the Sicilian Channel and beyond. Their movements and interactions helped shape marine communities over millennia. With their numbers now critically low, researchers worry that their absence will echo across the ecosystem, possibly leading to overpopulation of certain species and the decline of others — a classic cascade effect with long-term consequences.

Conservation Efforts and Scientific Challenges

Scientists are racing to understand where, if any, remnants of Mediterranean great white populations persist. Projects like tagging and observing sharks in the Sicilian Channel aim to gather data on movements, habitats, and population structure. Yet even these efforts are hampered by the species’ rarity; researchers have noted difficulty attracting sharks for tagging altogether, signaling just how scarce they have become.

Collaborative efforts between European, North African, and Middle Eastern nations are seen as essential to conserving these sharks. Conservation groups advocate for shared monitoring, better enforcement of existing bans, and deeper engagement with fishing communities to promote sustainable practices. Public awareness campaigns and reporting platforms also aim to involve citizen scientists in tracking sightings and contributing valuable information.

Even with these initiatives, the path to recovery is uncertain. Recovery of apex predators that have declined drastically often requires long-term commitment and multifaceted strategies that address habitat protection, fishing practices, and regional cooperation. Without such measures, the decline may continue unchecked.

Broader Regional Context: Sharks Across the Mediterranean

Great whites are not the only shark species in peril. The Mediterranean Sea hosts dozens of shark and ray species, many of which are also threatened by fishing and habitat degradation. A comprehensive analysis of conservation status across the region found that a significant proportion of cartilaginous fishes — sharks, rays, and related species — are listed as vulnerable, endangered, or critically endangered.

Despite more than 200 measures intended to protect these animals across 22 coastal states, enforcement varies widely. Sharks are increasingly reported as either targeted or incidental catch, reflecting both direct demand and the challenges of mitigating bycatch in busy fisheries. Conservationists emphasize that regional coordination and standardized reporting are necessary to effectively protect all vulnerable species.

What Can Be Done?

Experts believe that reversing the decline of Mediterranean great whites will require more than legislation; it necessitates community participation, economic incentives for sustainable fishing, and scientific investment. Training local fishers in less harmful methods and providing financial support can reduce reliance on shark catches. Additionally, technologies like environmental DNA sampling and citizen science reporting can enhance monitoring where traditional surveys fall short.

Stronger multinational cooperation, harmonized regulations, and effective enforcement remain at the heart of any viable recovery strategy. Conservationists hope that by working together, countries bordering the Mediterranean can create a refuge where great white sharks — and the broader marine ecosystem — can begin to recover.

The plight of great white sharks in the Mediterranean Sea is a stark reminder of how human activities can drive even the mightiest species toward local extinction. Decades of overfishing, weak enforcement of protections, and ongoing illegal catches have left this iconic predator critically endangered in a region where it once thrived. While some initiatives offer hope for recovery, time is short. Coordinated efforts — combining strong policy implementation, community engagement, and scientific research — are urgently needed to ensure these sharks remain part of the Mediterranean’s underwater world for generations to come.