Imagine standing face-to-face with a creature whose teeth looked more like daggers than anything you’d ever seen in the animal kingdom. Saber-toothed cats ruled the wild long before housecats curled in our laps, yet their story still stirs our curiosity and awe. These ancient predators, with their legendary saber-shaped fangs, spark visions of vanished worlds and the fierce beauty of nature at its wildest. Today, their fossils whisper secrets about survival, extinction, and what it truly meant to be a feline in the age of giants.

The Iconic Saber Teeth

Indeed, those iconic, scimitar-like fangs were nature’s ultimate precision blades—evolution’s answer to bringing down megafauna like mammoths and giant bison. Unlike modern big cats that suffocate prey with throat bites, the saber-tooth’s elongated canines were built for a single, devastating strike: sliding between ribs or severing arteries with surgical force. Yet these lethal weapons came at a cost; too rough a struggle could snap them, forcing the cat to rely on brute strength and grappling to immobilize prey first. A paradox of fragility and ferocity, those legendary teeth whisper of a hunting style as dramatic as it was dangerous—a high-stakes game where every kill walked the edge between feast and famine.

A Family of Fierce Hunters

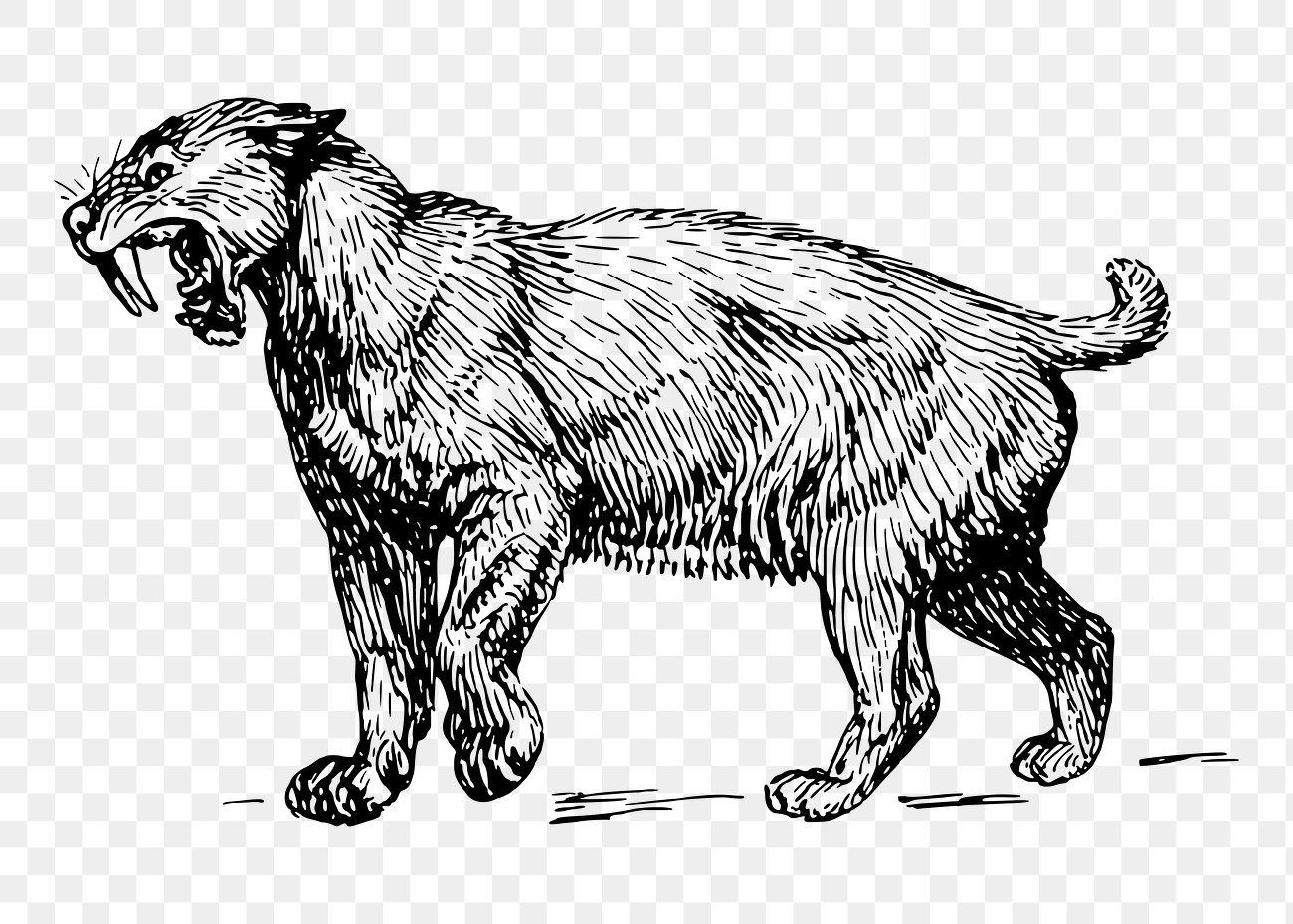

Absolutely! The saber-toothed cat family was a spectacular experiment in evolutionary engineering—a dynasty of predators that shaped ecosystems across continents. Smilodon, the iconic bulk-built ambusher, wielded its colossal fangs like a butcher’s cleaver, while Homotherium, the “scimitar cat,” was a lanky, endurance hunter built for chasing prey under open skies. Even lesser-known cousins like Megantereon or Xenosmilus carved out niches with unique blends of speed and power. Together, they prove evolution’s genius: when it finds a winning strategy (in this case, stab-first-ask-questions-later), it iterates, tweaks, and unleashes a kaleidoscope of deadly variations. Their diversity whispers a thrilling truth—that even the apex predator blueprint is never finished, only endlessly refined by time’s relentless tinkering.

Built for Strength, Not Speed

These prehistoric powerhouses were the armored tanks of the predator world—broad-shouldered, thick-necked, and built to overpower struggling megafauna in close-quarter combat. Imagine Smilodon‘s hunting style: an ambush explosion of muscle, pinning a giant ground sloth or bison with bone-crushing forelimbs before delivering that infamous precision bite to the throat. Their robust skeletons reveal adaptations for extreme grappling—collarbones like grappling hooks, lumbar vertebrae locked for stability, and forelimbs capable of twisting prey into submission. This was a cat that traded the cheetah’s 60-mph sprint for the raw, deliberate strength of a apex wrestler—proving that in the ice age’s brutal arena, sometimes slow and steady won the race… by breaking its neck.

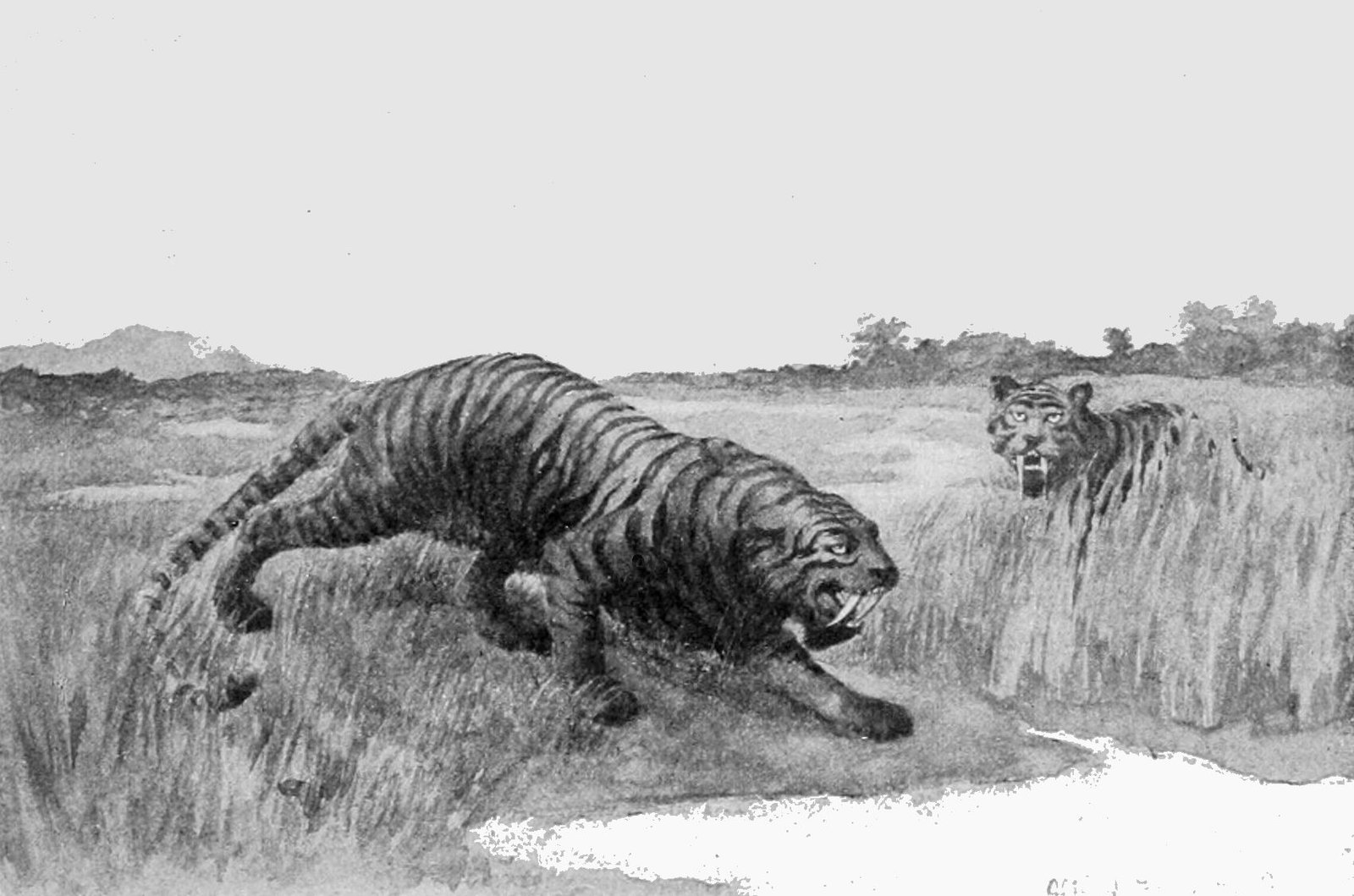

The Art of the Ambush

They were the ultimate ambush assassins—creatures of calculated stillness, their tawny coats melting into the golden grasslands as they waited hours for the perfect moment to strike. No sprinters, these cats; their strategy was one of explosive intimacy. A burst of muscle, a grapple of hooked claws, and then—the coup de grâce: those infamous fangs plunging deep between vertebrae or into a windpipe, avoiding bone that could snap their precious blades. Fossilized skulls show reinforced jaws capable of yawning open to 120 degrees, a gape that turned their head into a living guillotine. This was killing refined to an art form: slow, silent, and utterly intimate. The prey’s last sight? A dark muzzle flecked with hot breath, framing twin daggers descending with terrible, elegant finality.

Prey of the Past

Every hunt was a high-stakes duel against nature’s titans—a Smilodon launching itself onto the flanks of a woolly mammoth, clinging like a shadow as the beast trumpeted and staggered, or a Homotherium pack dragging down a snorting, dagger-horned bison twice their weight. These weren’t tidy kills; they were epic, messy battles where a single misplaced bite or kick could shatter fangs or ribs. Prey fought back with tusks, horns, and brute force, turning meals into gladiatorial spectacles. Fossil sites reveal the cost: healed fractures in saber-tooth bones, and the occasional fang snapped clean—proof that dinner came with a price. Yet for millions of years, this dance of tooth versus tusk worked, until climate change rewrote the rules and left the cats without partners. The ice age’s buffet of giants vanished… and so, too, did its most specialized diners.

Expressions Frozen in Time

Those reconstructed faces—wrinkled snouts, flared nostrils, and heavy brows frozen in a perpetual glare—hint at a creature of startling expressiveness. Fossilized skulls, with their wide zygomatic arches and deep-set eye sockets, suggest a face built for communication: perhaps silent lip-curls to warn rivals, or subtle ear twitches coordinating ambushes. Artists often lean into their dramatic potential, painting them with sun-dappled fur and eyes narrowed in predatory focus, or lips peeled back to expose fangs in a challenge that echoes across 12,000 years. But the most haunting renditions? Those that capture quieter moments—a mother gently gripping her cub’s scruff, or a lone male pausing to scent the wind, his face alive with something we can almost, almost recognize: curiosity, resolve, or the weight of solitude. Science gives us bones; art dares to give them back their souls.

Living in Ancient Packs?

The discovery of Smilodon fossils clustered together—some with healed injuries that would’ve required months of shared care—paints a provocative picture: perhaps these weren’t always solitary specters, but cats that knew the strength of numbers. Imagine a moonlit hunt where coordinated strikes brought down a mastodon, their iconic fangs used in concert like a pride’s synchronized ambush. Fossilized trackways in Argentina even show multiple saber-tooths moving in the same direction, hinting at pack behavior.

Yet their social structure likely differed from lions—more flexible, perhaps, with temporary alliances forming around mega-prey too dangerous for one. A wounded Homotherium with a healed broken leg suggests its clan brought it food while it recovered. If true, these cats weren’t just bone-crushing killers; they were comrades, caregivers, and tactical hunters whose survival may have hinged on the very thing their fangs seemed to deny: trust.

From Forests to Open Plains

These apex predators were ecological chameleons—thriving in the misty forests of prehistoric Florida, the arid scrublands of California’s La Brea, even the frigid edges of Pleistocene glaciers. Smilodon fatalis lurked in shrub-covered valleys, while its leaner cousin Homotherium prowled open steppes like a ghostly specter of the northern latitudes. Their remains tell a story of versatility: teeth adapted to different prey, limb proportions tuned for ambush or pursuit, and social behaviors shaped by habitat. From the humid jungles of South America to the windswept plains of Eurasia, they proved that the saber-tooth blueprint wasn’t a rigid design, but a template tweaked by evolution to dominate nearly every corner of the ancient world—until the very landscapes they mastered vanished beneath their paws.

The Mystery of Extinction

The extinction of saber-toothed cats remains one of paleontology’s most tantalizing mysteries—a perfect storm of shifting climates, disappearing megafauna, and the rising shadow of a new competitor: us. As glaciers retreated and grasslands transformed, their supersized prey—mammoths, giant sloths, and prehistoric bison—faded away, leaving these specialized hunters with empty stomachs and shrinking territories. Meanwhile, early humans encroached on their domains, possibly stealing kills or hunting the same dwindling herds.

Yet the truth may be even more haunting: they didn’t just fail to survive—they were unfit for the new world rising around them. Their colossal fangs, perfected over millennia for taking down giants, became obsolete in an era of smaller, swifter prey. Fossil layers tell the grim finale: Smilodon’s last known bones lie beneath a layer of volcanic ash in Ecuador, while Homotherium clung on in Arctic isolation until just 28,000 years ago—a ghost of its former glory.

Fossils in the Tar Pits

The La Brea Tar Pits are a predator’s paradox—a deceptively still surface that swallowed mammoths, dire wolves, and saber-tooths alike, transforming a death trap into a time machine. Over 2,000 Smilodon bones have been pulled from the black ooze, many clustered around the remains of trapped herbivores, revealing their fatal attraction to struggling prey. These weren’t careless hunters; they were opportunists lured by distress calls, only to become part of the buffet themselves.

The tar’s magic lies in its cruelty—it preserved not just bones, but moments. A cub’s skeleton curled near an adult’s suggests a family unit. Healed fractures hint at hard-lived lives. And the sheer number of predators—outnumbering prey 9-to-1—paints La Brea as a Ice Age “predator trap,” where desperation turned the tables on the hunters. Here, in the very asphalt that doomed them, saber-tooths achieved immortality: their bones, still bearing tooth marks from scavengers, now whisper secrets we’re only beginning to decode.

The Power of the Bite

Nature crafted saber-toothed cats as precision killers rather than powerhouses—their bite force paled in comparison to modern lions, but their jaws were engineered for something far more lethal. Like biological switchblades, their skulls could yawn open to an astonishing 120 degrees, allowing those iconic fangs to plunge between vertebrae or into soft throat tissue with surgical accuracy. This wasn’t about brute strength, but about perfect placement: a single, devastating strike to vital areas that turned their seemingly fragile teeth into ultimate killing tools. Their entire hunting strategy revolved around this delicate but deadly balance—evolution’s gamble that paid off for millennia until their giant prey disappeared.

Kittenhood in the Ice Age

Paleontologists imagine saber-toothed cubs as fuzzy, oversized kittens—clumsy paws batting at bones, mock-biting siblings, and shadowing their mothers through golden grasslands as they learned the art of ambush. Fossilized trackways show small paw prints mingling with adult ones, suggesting prolonged care in a world where play was practice for survival. A Smilodon cub’s skeleton from La Brea, its milk teeth still intact, hints at the vulnerability of youth; those iconic fangs took years to fully erupt, leaving juveniles dependent on protection and shared kills. These weren’t just miniature predators—they were students of an Ice Age curriculum, where every pounce perfected the lethal precision their species would need to wrestle giants.

The Soft Side of a Killer

Beneath their fearsome fangs, saber-toothed cats likely shared moments of quiet tenderness—grooming away the blood of a hunt with rough tongues, or curling together in sheltered dens to conserve precious body heat. Fossilized remains of injured adults with healed bones suggest they may have relied on their group for care, just as modern lions do. Imagine a Smilodon mother nuzzling her cubs at dusk, or two males dozing shoulder-to-shoulder after a failed chase, their rivalry momentarily softened by exhaustion. Even the ice age’s most specialized killers weren’t just teeth and muscle—they were creatures of instinct and intimacy, whose lives pulsed with the same warmth that still beats in every living feline today.

Fur Patterns Lost to Time

The true colors of saber-toothed cats remain one of paleontology’s most tantalizing mysteries—their fur patterns lost to time, leaving artists to weave educated guesses from the shadows of modern predators. Perhaps Smilodon wore a tawny lion-like mane to intimidate rivals, or maybe it sported snow leopard-like rosettes for stalking through dappled woodlands. Some reconstructions dare to imagine them with striking tiger stripes or the subtle gradient of a cougar’s coat, each interpretation breathing life into their fossilized forms.

What we do know? Their environment likely shaped their camouflage—open plains favoring muted tones for ambush, while forest-dwellers might have needed disruptive patterns. Until science uncovers melanin traces in their fossils, these cats will continue to shape-shift in our imaginations, their true beauty as elusive as the hunting strategies that made them legends.

Eyes for the Hunt

The cavernous orbits of saber-toothed cat skulls hint at eyes specially adapted for twilight’s fleeting magic—when the fading sun stretched shadows long and prey moved with vulnerable urgency. These weren’t just large eyes, but precision instruments packed with light-sensitive cells, capable of detecting the slightest twitch of a woolly rhino’s ear or the panicked flare of a horse’s nostrils in the gloaming. Like modern big cats, they likely possessed a reflective tapetum lucidum, turning their gaze into shimmering beacons that pierced the half-light with predatory clarity. Evolution armed them not just with dagger teeth, but with visual acuity that transformed dusk’s ambiguity into a tactical advantage—where every fading ray illuminated opportunity.

Sound and Silence

Imagine the deep, resonant thrum of a saber-toothed cat’s roar vibrating through Pleistocene valleys—a sound that may have been less a lion’s thunder and more a bone-deep, guttural pulse, optimized to carry across open tundra or through dense forests. Fossilized hyoid bones in Smilodon suggest a voice box capable of powerful vocalizations, perhaps used to stake territory across vast hunting grounds or coordinate with kin in the dark.

Did they purr when content? Snarl with a frequency that made mammoths flinch? We’ll never know the exact timbre of their lost language, but in cave art, they’re often depicted mouths agape—as if the artists who revered them could still hear their phantom cries echoing long after the cats themselves were gone. Their silence today is an irony: creatures so visually iconic, yet voiceless in the fossil record.

Legends in Human Culture

The ghostly presence of saber-toothed cats lingers in the ochre strokes of prehistoric cave art—their fangs etched with such visceral detail that some scholars wonder if humans watched them hunt, or even stole their kills. Fossil evidence from sites like Schöningen in Germany places early humans and Homotherium in the same icy landscapes, suggesting a relationship woven from both fear and fascination.

Did shamans mimic their ambush tactics? Were their pelts trophies, their teeth talismans? The way ancient artists depicted them—muscles taut, lips curled—hints at more than observation; it speaks of a primal recognition between one apex predator and another. These cats weren’t just part of the environment—they were rivals, teachers, and perhaps even spiritual figures whose extinction left humans as the sole inheritors of a world once shared.

Survival Lessons in Bones

Every fossil whispers a tale of survival—cracked teeth from desperate meals, bones mended against all odds, and creatures thriving on the razor’s edge of existence. These ancient remnants reveal not just individual struggles, but entire ecosystems shaped by hunger, competition, and sheer endurance. Through them, we glimpse the relentless resilience of life, where every scar and fracture holds lessons about adaptation and survival against impossible odds. They remind us that the past was not just a time of giants, but of fighters who weathered storms we can scarcely imagine.

Conservation’s Ancient Roots

The fate of the saber-toothed cat is a haunting lesson—a once-dominant predator brought to extinction by shifting climates, vanishing prey, and shrinking habitats. Their disappearance echoes today as modern big cats, wolves, and other apex predators face similar threats from human activity and environmental change. Their story warns us that no species, no matter how fierce or adaptable, is invincible when ecosystems unravel. Protecting today’s vulnerable wildlife isn’t just about saving individual species—it’s about preserving the delicate balance that sustains all life, before more chapters of Earth’s history close forever.

The Science of Discovery

Every fresh fossil discovery peels back another layer of the saber-toothed cat’s mysterious past, revealing unexpected adaptations, behaviors, and evolutionary twists. From recent findings of different hunting strategies to evidence of social structures, these ancient predators were far more complex than we ever imagined. Each unearthed bone and tooth forces us to rethink old assumptions, proving their history was richer and more dynamic than textbooks once claimed. The saber-tooth’s story isn’t set in stone—it’s a living narrative, still being written by the very ground beneath our feet.

DNA: Unlocking Ancient Secrets

Though time has shattered their genetic blueprint, scientists are piecing together the saber-tooth’s evolutionary puzzle through ancient proteins and fragmentary DNA preserved in fossils. These molecular whispers hint at surprising kinships—not just with modern big cats, but with enigmatic prehistoric hunters like the scimitar cat. Each biochemical clue rewrites branches on the feline family tree, showing how these iconic fangs evolved multiple times across millennia. Even without a complete genome, these genetic ghosts remind us that every living cat carries echoes of their saber-toothed cousins’ legacy.

Inspired by Giants

With their dagger-like fangs and powerful presence, saber-toothed cats have leapt from fossils into our collective imagination—starring in cave paintings, blockbuster films, and childhood dinosaur books alike. They embody nature’s dramatic flair, a perfect blend of beauty and ferocity frozen in time. Artists and storytellers keep them alive, reimagining their roars, their hunts, and their icy world lost to history. More than just extinct predators, they’ve become timeless symbols of wilderness’s untamed majesty, inspiring awe across generations.

Lasting Impressions in Stone

These magnificent Ice Age hunters bridge the gap between myth and reality—their curved fangs resting in museum displays seem almost too dramatic to be real, yet their bones tell undeniable truths of a vanished world. Whether displayed under soft museum lights or half-buried in ancient sediment, each fossil is a puzzle piece waiting to reveal secrets about survival, extinction, and evolution. Running a finger along the groove of a saber tooth or studying the healed fracture in a massive limb bone, we make an intimate connection with creatures that walked the earth thousands of centuries ago. They are not just relics, but storytellers—and their tale of adaptation and ultimate demise grows richer with every specimen we uncover.

Wonder, Loss, and Legacy

These magnificent predators danced on nature’s razor edge for millions of years—their curved fangs a masterpiece of evolution, their muscular bodies honed by relentless Ice Age challenges. Yet their ultimate disappearance whispers a sobering truth: even the most perfectly adapted creatures are vulnerable when the world changes too fast. Today, as we marvel at their fossilized grandeur and see echoes of their spirit in modern prowling big cats, the saber-tooths become more than ancient bones—they transform into living symbols. They remind us that extinction isn’t just about loss, but about the fragile, sacred thread connecting all life across time—a thread we must protect with wiser stewardship of our planet’s remaining wild wonders.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Feline Fam, where he channels his curiosity for the Feline into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.