In Argentina’s windswept Patagonia region, a remarkable ecological shift is unfolding that has surprised scientists: large wild cats known as pumas have begun preying on Magellanic penguins, and that dietary change is reshaping how these predators behave. In Monte León National Park, where pumas have returned after decades away, researchers have watched the cats take advantage of a dense penguin breeding colony, a scenario that was virtually unheard of before. The unexpected predator-prey relationship is challenging long-held assumptions about puma ecology and offers fresh insights into how restored ecosystems function.

A Rare Predator-Prey Encounter Along the Patagonian Coast

Pumas (Puma concolor), typically associated with forest, grassland and mountainous terrains from North to South America, have historically not encountered large ground-dwelling seabirds as regular food sources. That has changed in Monte León National Park, where a thriving colony of Magellanic penguins—numbering in the tens of thousands—breeds on coastal sands each year. With the reappearance of pumas following the park’s establishment and protection, these big cats have begun incorporating penguins into their diet, a behavior that stands out amid their usual repertoire of deer, smaller mammals and birds.

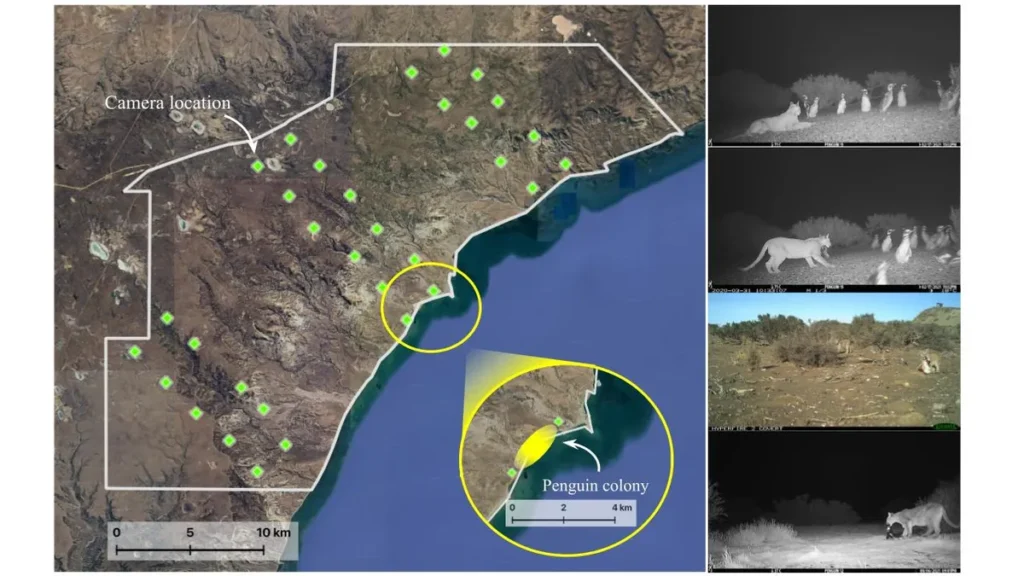

Researchers used GPS tracking collars and camera traps to document pumas hunting and consuming penguins during the birds’ breeding season, when adults and chicks are concentrated onshore and unable to flee into the sea. The sheer accessibility and abundance of penguins have turned this seabird colony into an unexpected food hotspot for the terrestrial predators.

Behavioral Shifts Among Pumas Triggered by a New Food Source

One of the most striking findings from the study is the way puma behavior has shifted in response to penguin availability. Pumas are normally solitary and territorial, keeping wide ranges to secure enough prey. However, those that have been taking advantage of the penguin colony are frequently found in close proximity to one another, showing a surprising tolerance for neighbors. This increased spatial overlap stands in contrast to their typical behavior and suggests that abundant, concentrated food can relax territorial instincts even in apex predators.

During the months when penguins are present, pumas tend to shorten their travel distances and spend more time around the colony. When the penguins migrate back to sea outside of the breeding season, the cats expand their range again and resume more typical solitary movement patterns. These shifts hint at a dynamic flexibility in puma ecology driven by resource distribution.

How Conservation Efforts Set the Stage for Novel Interactions

Monte León National Park was once dominated by sheep ranching, which drove pumas and other large wildlife out of the landscape. Since the park’s creation in 2004 and ongoing management efforts to preserve native habitats, pumas have gradually re-established themselves. Meanwhile, penguins—historically found mostly on offshore islands—have formed a large continental breeding colony in part because of the reduced presence of predators.

This convergence of recovering predator and abundant prey illustrates the unintended consequences of ecological restoration. While reintroducing or protecting species can bring back lost biodiversity, it also can create novel relationships that don’t necessarily reflect historical interactions. Ecologists argue that understanding these new dynamics is essential for effective conservation planning in a changing world.

Ecological Ripples: Beyond Penguins and Pumas

The impact of penguin-eating behavior may extend beyond the two species directly involved. A plentiful food supply has the potential to support a denser puma population than would otherwise be possible, which could influence predation pressure on other native species such as guanacos—a camelid that has long been a staple in the puma diet. Researchers plan to examine whether pumas’ reliance on penguins changes their impact on traditional prey and overall ecosystem balance.

There is also interest in how pumas’ new feeding habits might affect penguin colonies themselves. Large, established colonies may withstand predation without dramatic decline, but smaller colonies or newly founded ones could be more vulnerable. These ecological feedbacks highlight the complexity of managing an ecosystem where historical patterns have shifted.

What This Tells Us About Wildlife Flexibility

This unusual scenario underscores the adaptability of both predators and prey when habitats and species distributions shift. Pumas have demonstrated a remarkable ability to exploit a previously untapped food resource, while penguins have settled in areas that once seemed unlikely for breeding due to historic predator pressure. The interplay between conservation success and ecological innovation raises important questions about the future of restored ecosystems.

Experts suggest that these findings offer a broader lesson in ecology: protecting species and habitats can yield unexpected outcomes that science must be prepared to understand and address, rather than simply seeking to restore historical conditions.

The discovery that pumas in Patagonia not only hunt penguins but also change their behavior as a result illuminates the ever-evolving nature of ecosystems. Fueled by conservation progress and the reintroduction of top predators, this rare predator-prey interaction challenges assumptions about species roles and underscores the need for nuanced wildlife management strategies. As ecosystems continue to adapt to human influence and restoration efforts, scientists emphasize that ongoing research will be vital to anticipate and respond to these complex ecological stories